The pamphlet that accompanies the exhibition on Italian art in Fascist Italy is provocative and augurs well for a good two hours of art enjoyment. The exhibition does not deliver all that it promises. Guardian art critic Jonathan Jones contends that far from showing 1930s Italian art as a cauldron of experimentation, it takes the viewer through a “bleak journey into the aesthetic lifelessness of a totalitarian society”.

The day I visited the exhibition (November 24) I overheard snippets of conversation, some of which

echoed my own impressions while others seemed unduly harsh. Here is a sample:

I understand that the Fascists didn't have a strict policy on art like the Nazis or Stalin did...

No guidelines, no style privileged over another, no particular theme, no explicit political message...strangely liberal for Mussolini.

What happened if the state decided it didn't like a particular work of art?...

I'd have been nervous about producing anything and entering any work in those state-sponsored competitions...

They were allowed to experiment but nobody did...

So much of it looks like work by other artists from other places...like these Van Gogh-like paintings.

It's worth bearing in mind that what we are seeing was filtered by decisions made by a curator in 2012...

In the end, I'm not sure the exhibition has much to say about Fascism at all, at least not more than it has to say about the limiting effect of employing art as an extension of state...

This stuff was not asked to do much and it does very little. Not like those great big, colourful Soviet posters we see from time to time..they're beautiful even if they were ideologically driven and heavy-handed.

If the art had been hung up somewhere and just the dates of the paintings and the names of the artists were posted, I bet that most people would say that this was an exhibition of amateur art in the Depression era in Italy...

My verdict: the little posters punctuating the exhibition which told the personal stories of people who lived through the decade were charming but too many of the paintings lacked “soul” - and perhaps that is what made them representative of the Fascist decade in Italy.

ANNI '30 - The Thirties The Arts In Italy Beyond Fascism is at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence from 22 September 2012 to 27 January 2013

Follow @deltorniv

Sunday 9 December 2012

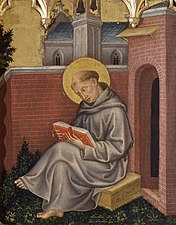

Atheism in Modern History by Gavin Hyman (2007)

There is a brilliant essay in the Cambridge Companion to Atheism written by Gavin Hyman entitled Atheism in Modern History that should be read by anyone who is interested in the historical and theoretical movements that have shaped western religion. This essay is not easy, it assumes a familiarity with philosophical concepts but it is cleverly structured and it defines and clarifies ideas as it moves along.

It begins with the story of a witch-hunt that occurred in France in 1632 — an event which is emblematic of the “trauma of the birth of modernity” because its failure represents the confrontation of a society with the certainties it is losing (theism, faith) and those it is attempting to acquire (modernity).

The next section describes how medieval theism develops into “secularism”, “agnosticism” and “atheism” of all stripes, citing the important cultural developments which precipitated these shifts in thought. The core of the essay, the thesis, resides in the idea that medieval theism, the one espoused by Thomas Aquinas did not and could not have conceived of atheism as we know it today and that it was the work of one unwitting Duns Scotus (a monk!) which so shifted the theological/philosophical paradigm that the possibility of doubt was introduced into Christian thought.

Essentially, the Thomistic idea that God is “transcendent”, forever apart and therefore always unknowable to us was compromised by Duns Scotus and those who followed. Before, only Divine revelation which was of course, only God's prerogative, could allow us a glimpse into His nature. Then came the revolution — God was not “transcendent”, He could indeed be apprehended by us: we now saw that we shared in God's nature. He was infinite and we were finite, He was omnipotent and we were not, of course, of course — but now, the terms by which we could describe Him and our relationship to Him could be “clear and distinct”. We could apply logic to the question, we could use scientific evidence, archaeological findings, we could bring the force of our learning to the study of God and religion in order to get closer to Him. Or, we could use Enlightenment tools to doubt and to build new explanations for our existence...

There is much to recommend this essay to believers and non-believers alike. Bravo to Professor Hyman. Follow @deltorniv

It begins with the story of a witch-hunt that occurred in France in 1632 — an event which is emblematic of the “trauma of the birth of modernity” because its failure represents the confrontation of a society with the certainties it is losing (theism, faith) and those it is attempting to acquire (modernity).

The next section describes how medieval theism develops into “secularism”, “agnosticism” and “atheism” of all stripes, citing the important cultural developments which precipitated these shifts in thought. The core of the essay, the thesis, resides in the idea that medieval theism, the one espoused by Thomas Aquinas did not and could not have conceived of atheism as we know it today and that it was the work of one unwitting Duns Scotus (a monk!) which so shifted the theological/philosophical paradigm that the possibility of doubt was introduced into Christian thought.

Essentially, the Thomistic idea that God is “transcendent”, forever apart and therefore always unknowable to us was compromised by Duns Scotus and those who followed. Before, only Divine revelation which was of course, only God's prerogative, could allow us a glimpse into His nature. Then came the revolution — God was not “transcendent”, He could indeed be apprehended by us: we now saw that we shared in God's nature. He was infinite and we were finite, He was omnipotent and we were not, of course, of course — but now, the terms by which we could describe Him and our relationship to Him could be “clear and distinct”. We could apply logic to the question, we could use scientific evidence, archaeological findings, we could bring the force of our learning to the study of God and religion in order to get closer to Him. Or, we could use Enlightenment tools to doubt and to build new explanations for our existence...

There is much to recommend this essay to believers and non-believers alike. Bravo to Professor Hyman. Follow @deltorniv

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)